.:Aktuelles

"Change". Momentum of its own in pre-modern Latin America

Organizers: Franz-Josef Arlinghaus, Eleonora Rohland und Andreas Rüther

Call for Papers - Change. Momentum of its own in pre-modern Latin America

Organizers: Franz-Josef Arlinghaus, Eleonora Rohland und Andreas Rüther

Abstract — The explicit aim of this conference is to trace the meaning of 'momentum of its own' in pre-modern Latin America.

We assume that pre-modern societies share common structural elements that continued to represent drivers of change.

To capture this, we adapt the theoretical concept of 'momentum of its own' (‘Eigendynamik’) or ‘inherent dynamism’.

If this aim appeals to you, please send an abstract of 500-800 words to franz.arlinghaus@uni-bielefeld.de until March 25, 2023.

CfP — With this conference, we would like to explore two theses: First, we assume that pre-modern societies share common structural elements that continued to represent drivers of change.

To capture this, we adapt the theoretical concept of 'momentum of its own' (‘Eigendynamik’) or ‘inherent dynamism’ for our period of investigation. Second, we postulate that such a momentum was inherent in many pre-modern societies. In this way, we question the widespread and politically relevant view that, in the pre-modern period, there were fundamental differences in the affinity for change in one region of the world or another. Further on, we would like to stim-ulate research towards a change of perspective:

It is less a development converging over centuries culminating in the present that emerges then. Rather, in pre-modern societies simi-lar impulses for change seem to be detectable, which first of all further shaped the structures of these societies themselves.

The concept of the conference is essentially based on the cooperation of eight scholars who have been discussing these theses for Ethiopia, Europe, and East Asia and have already held two conferences.

The explicit aim of this conference is now to trace the meaning of 'momentum of its own' in pre-modern Latin America. The Americas are of particular interest because this region of the world has to reckon with special historical constellations, both, be-fore and after European conquest and its forced inclusion in the economic and cultural ex-change with Africa and Europe. So, the question arises whether the concept of 'momentum of its own' applies here as well? Where would adjustments have to be made?

With 'momentum of its own' the conference mobilizes a widely discussed theoretical concept (initially developed in the context of 'Western modernity'), which, however, has expe-rienced little application in the pre-modern era in or outside of Europe so far. The basic idea of this approach is that processes drive change out of themselves, without however, affecting the underlying structures of society.

Our understanding of the concept leans on suggestions made by the German sociologists Renate Mayntz and Bettina Nedelmann who state that so-cial processes can be “described as inherently dynamic [if] they continue to move ... out of themselves and without further external influence, thereby producing and reproducing a pat-tern characteristic of them” (Mayntz/Nedelmann 1997, p. 87.).

According to the first charac-teristic, the ‘intrinsic’ feature of dynamics is that the decisive drivers for change arise from the processes themselves. Of course, momentum of its own also rests on the actions of actors; however, momentum processes are able to motivate individuals to participate in and sustain these very processes.

The definition aims at identifying a certain number of relevant processes for a given situa-tion, which together carry a concrete momentum of their own. These processes can be locat-ed both inside and outside a geographical or social unit. What is particular in this conception of ‘momentum of its own’ are not the social or geographical spaces, but the processes yet to be concretely identified.

The latter need to be determined for each object of investigation. Evidently, the concept of 'momentum of its own' needs some adaptation to the specifics of the societies existing during the period and presumably in the geographical spaces under investi-gation.

In line with the relevant historical research, we identified three structural elements: 1) estate-based hierarchical order of societies with group orientation, 2) culture of presence, and 3) consensus orientation.

1) Estate-based hierarchical order and group orientation: We assume that the efforts of indi-viduals as well as groups to constantly assert their own position in the status-oriented, es-tate-based hierarchical structure and, if possible, to improve it, constituted an essential el-ement of self-dynamic processes.

At the same time, the establishment of groups, (wheth-er noble familia, clan, religious communities or guilds), is a process in the course of which, for example, forms of demarcation and outdoing were repeatedly renegotiated. In this process, the estate-based hierarchical order of society, which was transcendentally legit-imized, formed the hardly changeable structural principle along which the historical actors oriented their actions.

Where, however, the individual person or group was to be placed, who belonged to this or that association, was repeatedly retold and performatively deter-mined. Thus, group dynamics are fed not least by the tension between an ideal, fixed, hi-erarchical order and the openness of its daily implementation.

2) Presence culture: In the joint presence of the actors, processes of change acquire their own specific form, because the perception of body and clothing, especially when com-bined with per¬formances and rituals, shaped communication in a special way. Historical research on rituals as well as on the use of media in premodern times has gained a broad international basis over the last few decades.

However, research so far has hardly ad-dressed the connection between a culture of presence and social change. On the one hand, copresence is itself susceptible to its own dynamics. On the other hand, gatherings are able to put their own stamp on momentums of its own. What is more, literacy is not in contradiction to this, but in a productive relationship.

As recent research has shown, in our period of investigation it can be seen as an enrichment of the modes of communication of the general culture of presence.

3) Consensus orientation:Unanimity seems to have a normative character in most Europe-an pre-modern societies. Tolerance for dissenting positions was very low; against the background of a general drive towards consensus orientation, they could hardly claim le-gitimacy for themselves. Often, 'rebellion' or 'tyranny' were the dominant categories with which controversies were mapped. Thus, neither the absence of conflict nor the ideas of a 'harmonious society' are meant by 'consensus orientation'.

The dispute, to which Simmel already assigned a momentum of its own, was virtually framed by a consensus orienta-tion, because dissent was hardly considered legitimate.

In this respect, consensus orien-tation is to be taken into account as a parameter, for instance, in negotiations as well as in the case of aspired increases in status. It did not prevent conflicts that tended toward in-herent dynamism; rather, it drove them forward and imposed a certain form on them.

Recent research on the European nobility emphasizes that positioning oneself and outdoing others as a practice was inherent in rank society sui generis (Peltzer 2015). The fact that momentum of its own form patterns, the second characteristic, does not mean that processes would always run identically.

To stay with positioning: Those who sought to consolidate or improve their position vis-à-vis others around 1500 used different performances and seman-tics, needed different skills than around 1300 (cf. Morsel 1997). Nevertheless, the need to position oneself within the estate-based hierarchical order was still required; the impetus and result of the changes resulted from the same processual foundations that drove momentum of its own.

With this conference we aim to take the concept of ‘momentum of its own’ out of its so far mostly European context of application in order to test its productivity and explanatory value in the societal context of pre- as well as post-Columbian South America.

We are hoping for new empirical but also theoretical insights with this setup and for exciting – and possibly con-troversial – discussions.

If this aim appeals to you, please send an abstract of 500-800 words to franz.arlinghaus@uni-bielefeld.de until March 25, 2023.

Selected literature

Mayntz, Renate & Nedelmann, Birgitta, Eigendynamische soziale Prozesse. Anmerkungen zu einem analytischen Paradigma, in: Renate Mayntz (Hg.), Soziale Dynamik und politische Steuerung. Theoretische und methodologische Überlegungen (Schriften des Max-Planck-Instituts für Gesellschaftsforschung Köln 29), Frankfurt/M. 1997, S. 86-114 (Erstaufl. 1987).

Morsel, Joseph, Die Erfindung des Adels. Zur Soziogenese des Adels am Ende des Mittelalters - das Beispiel Frankens, in: Otto Gerhard Oexle & Werner Paravicini (Hgg.), Nobilitas. Funktion und Repräsentation des Adels in Alteuropa, Göttingen 1997, S. 312-375.

Peltzer, Jörg, Introduction, in: Jörg Peltzer (ed.), Rank and Order. The Formation of Aristocratic Elites in Western and Central Europe, 500-1500, Ostfildern 2015, S. 13-37.

Deutungskämpfe - 53. Deutscher Historikertag

Sektionsleitung mit Franz-Josef Arlinghaus

Japan, Korea und Mitteleuropa. Sozialer Wandel in mittelalterlich-frühneuzeitlichen Gesellschaften im Vergleich

Franz-Josef Arlinghaus (Bielefeld, GER) und Andreas Rüther (Bielefeld, GER)

Abstract — Ausgangspunkt ist die Überlegung, dass sich in vormodernen Gesellschaften Japans, Koreas und Mitteleuropas

in der Zeit zwischen 12. und 18. Jahrhundert starke Veränderungen vollzogen haben, die von der Forschung vorwiegend aus

Anstößen hergeleitet werden, die in der jeweiligen weltregionalen Kultur begründet sein sollen.

Dagegen möchte die Sektion zur Diskussion stellen, ob sich für den sozialen Wandel, die Ostasien und Europa

vom Hochmittelalter an erfuhren, gleichartige Antriebe ausmachen lassen. Wir wollen ausloten, ob sich trotz

aller kulturellen Unterschiede im Aufbau dieser vormodernen Gesellschaften selbst gemeinsame Elemente identifizieren lassen,

die Veränderungen eingeleitet oder herbeigeführt haben. Die beispielsweise schon von Max Weber in Spiel gebrachten Ähnlichkeiten

im Aufbau genossenschaftlicher Verbände sind in Detailstudien zumindest für Japan bereits einer differenzierten Analyse unterzogen worden.

Ob und in wieweit können die Praktiken der Bildung und Binnendifferenzierung solcher Verbände sowie ihre Abgrenzung untereinander als Prozesse

verstanden werden, die weniger in den Kontakten der Weltregionen untereinander als vielmehr in ihren Strukturen selbst wurzeln?

Bei den in den Blick genommenen Weltregionen handelte es sich im genannten Zeitraum um mehr oder weniger ausgeformte ständische Gesellschaften,

die üblicherweise mit Inflexibilität und Starrheit assoziiert werden. Andererseits ist von zahlreichen Rangkonflikten zu berichten,

die mit erheblichen materiellen und personellen Mitteln betrieben wurden und zu Veränderungen im sozialen Gefüge geführt haben. Die Sektion möchte thematisieren,

ob nicht schon die ständisch-hierarchische Struktur selbst, die ja jeden Einzelnen und jede Gruppe zwingt, sich seinen/ihren Platz zu suchen (oder zu erstreiten),

ungeachtet des konkreten Anlasses insgesamt Veränderungsdynamiken auslöst. Ein weiteres Kennzeichen nicht nur des lateineuropäischen Mittelalters wie der Frühen Neuzeit

ist eine Konsensorientierung der Akteure, womit keine Abwesenheit, sondern andere Handhabe von Konflikten gemeint ist. Hinzu gesellt sich eine ausgeprägte Präsenzkultur

die der Anwesenheit der Akteure eine zentrale Bedeutung zuweist. Die Frage ist auch hier, ob nicht diese Art der Vergesellschaftung

eine spezifische Form des sozialen Wandels hervorruft, weil beispielsweise mit Konflikten bei Kopräsenz der Akteure anders umgegangen werden muss als bei deren Abwesenheit.

Wie und in welchem Maße trieben die genannten Phänomene in den jeweiligen westlichen und östlichen Kulturen sozialen Wandel voran?

Lassen sich bei diesem Wandel nicht nur hinsichtlich der Antriebe, sondern auch der Ergebnisse Gemeinsamkeiten feststellen?

Lassen sich aus dem anders gearteten Umgang mit Dissens ähnliche Formen der Konfliktregelung ableiten? Schließlich gilt es ebenso kritisch zu fragen,

ob es nicht weltregionale Spezifika gibt, etwa religiöser Art, die die Wirkung der genannten drei Momente ‚aushebeln‘ könnten.

Vortrag — Der Adel macht die Klöster reich … Soziale Antriebe zur Differenzierung von Dynastie und Orden im spätmittelalterlichen nordöstlichen Europa

Der Blick auf hochadelige Handlungsweisen und Motivlagen als Stifter und Wohltäter schließt Erkenntnisse für Veränderungsprozesse von sozialen Formationen

seit dem 12. Jahrhundert auf. Gemeinschaften von Klerikern, Mönchen und Nonnen sind auf ihre Funktion als Teilbereiche von dynastischen Geschlechtern hin zu befragen.

Aus der Zugehörigkeit zu nebeneinander angeordneten Personenverbänden wie Adelsfamilien, Klöstern oder Städten ergaben sich besondere Konstellationen,

die eine Dynamik auslösten und neue Formen hervorbrachten. Eine ‚relationale‘ Geschichte des Monastischen zeigt hierarchisch gegliederte Gruppenbildungen,

die sich durch Wettbewerb unter Herrschaftsträgern, die Präsenz am Hof, in Kirche und Stadt sowie Aushandlung von innewohnenden Konflikten ständig wandelten.

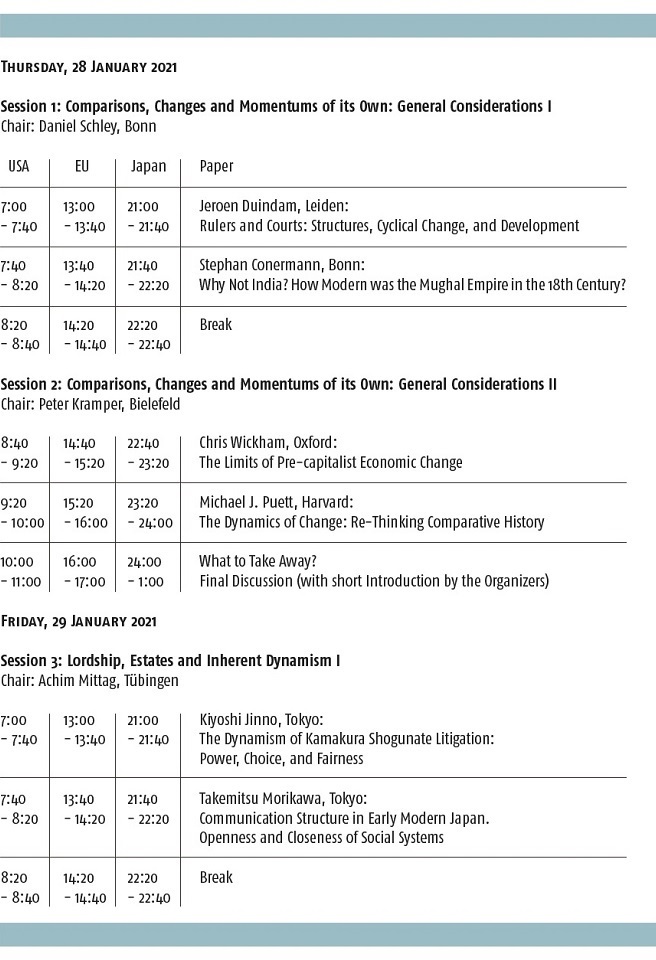

ZIF-Workshop

Momentum of its own

Inherent Dynamism in Pre-Modern Societies

Franz-Josef Arlinghaus (Bielefeld, GER), Andreas Rüther (Bielefeld, GER)

and Jörg Quenzer (Hamburg, GER)

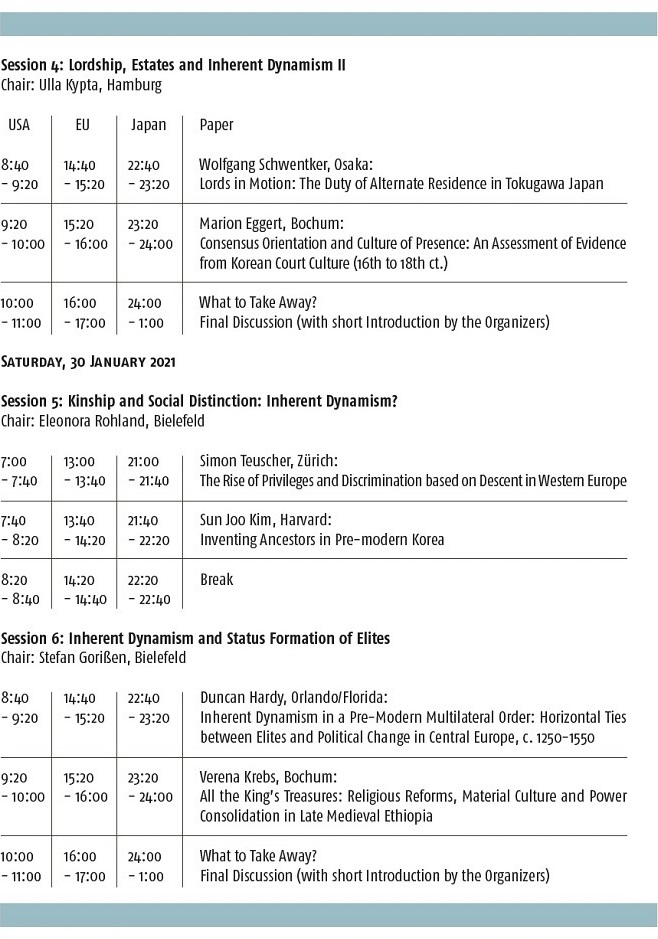

Thesis — The core thesis is that the basic structures of pre-modern societies show elements which are themselves

driving forces for a constant change of these societies. At the same time, the kind of change was of a

specifically pre-modern nature. In line with sociological theory, this can be called ‘inherent dynamism’. The

second assumption is that the continuous restructuring of the society leads to these structures becoming clearer.

In a way, pre-modern society came into its own only by the end of the period under observation (ca. 700

to ca. 1700), shortly before the comparably rapid emergence of a functionally differentiated modern age.

‘Inherent dynamism’ means that the phenomenon itself, e.g. by interplay of specifiable elements, caused

specific changes. In contrast to the term emergence, applied to an entity that has properties that its parts do

not have on their own, things brought about by inherent dynamisms can be traced back to features on which

the changes are based. And quite often the results of these changes follow certain patterns.

When working with inherent dynamism, a central point is to identify what belongs to these dynamisms

and what does not. To be sure, in some cases inherent dynamism may work within the limits of a certain

social entity. However, very different phenomena on both sides of the boundaries of such a unit may contribute

to self-propelled processes. Instead of looking for a social group or territory even, it seems more

adequate to identify a (limited) number of different, but important processes that together, as a cluster, lead

to such dynamisms.

Premises — We presume that most pre-modern societies of different world regions had a number of basic

structures in common and singled out three: First, membership in a group comprehensively determined

the overall quality of the person, and that groups and persons are arranged in an estates-based hierarchy.

Second, despite the ubiquity of (violent) conflicts, a general orientation to consensus (e.g. delegitimizing

dissenting opinions) can be observed. Third, a culture of presence that integrated the use of written texts was

another hallmark of these societies.

Among others, the three elements shaped pre-modern inherent dynamisms in a decisive way. Historicizing

the concept thus underscores the similarity of premodern societies with regard to their potential for

change and establishes a distance to similar phenomena in modernity.

We further assume that in most premodern societies, change over time resulted in increased complexity.

There was a growing number of groups and estates, but also an increase of qualitatively different associations

and ranks. At the same time, it seems as if both, associations and estates, gained a sharper profile. Nevertheless,

these changes took place within the structures stated above. Thus, it is not about writing a genesis

of modernity but about analysing change in pre-modern times as a genuinely pre-modern phenomenon.

Relevance — If self-propelled processes prove to be a crucial element shared by many pre-modern societies,

this will shed a new light on the relationship between the pre-modern and modern, and this twofold: First,

in pointing out fundamental similarities of pre-modern societies particularly concerning the driving force for

change. Second, in emphasizing that in no region these changes were immediately connectable to modernity;

on the contrary, they rather affirmed the structures of pre-modern societies. Thus, modernity itself is

contoured as a recent phenomenon which emerged rather suddenly. Further, this approach would help to

overcome particularistic narrations so ubiquitous in many world regions today.

Workshop — The situation only allows for a hybrid workshop, concentrating on discussion rather than on

paper-giving. Each talk will consist of summarizing a draft paper of six pages, circled beforehand, followed

by a discussion of approximately 35 minutes.